Queen Elizabeth’s Policies Resulted In Kenyan Freedom Fighters Living in Concentration Camps

The British Policies that led to the Imprisonment of the Mau Mau Resistors of Colonialism in Kenya.

The Mau Mau Uprising was a rebellion against British colonial rule in Kenya which lasted from 1952 to 1960 and assisted in securing Kenya’s independence. Some of the issues that resulted in the Mau Mau uprising included the displacement of Kikuyus from settler farms, loss of land to British settlers, poverty, and the absence of genuine political representation for Africans. During the eight-year Uprising, approximately thirty-two white settlers, two hundred British police, and army soldiers lost their lives. More than 1800 African civilians and 20,000 Mau Mau rebels were killed (Furedi, 1989). Even though the Uprising was directed mainly against British colonials and the white settlers, most of the war was between the Mau Mau rebels and loyalist Africans. Our goal is to discuss the British policies that led to the imprisonment of the Mau Mau resistors of colonialism in Kenya.

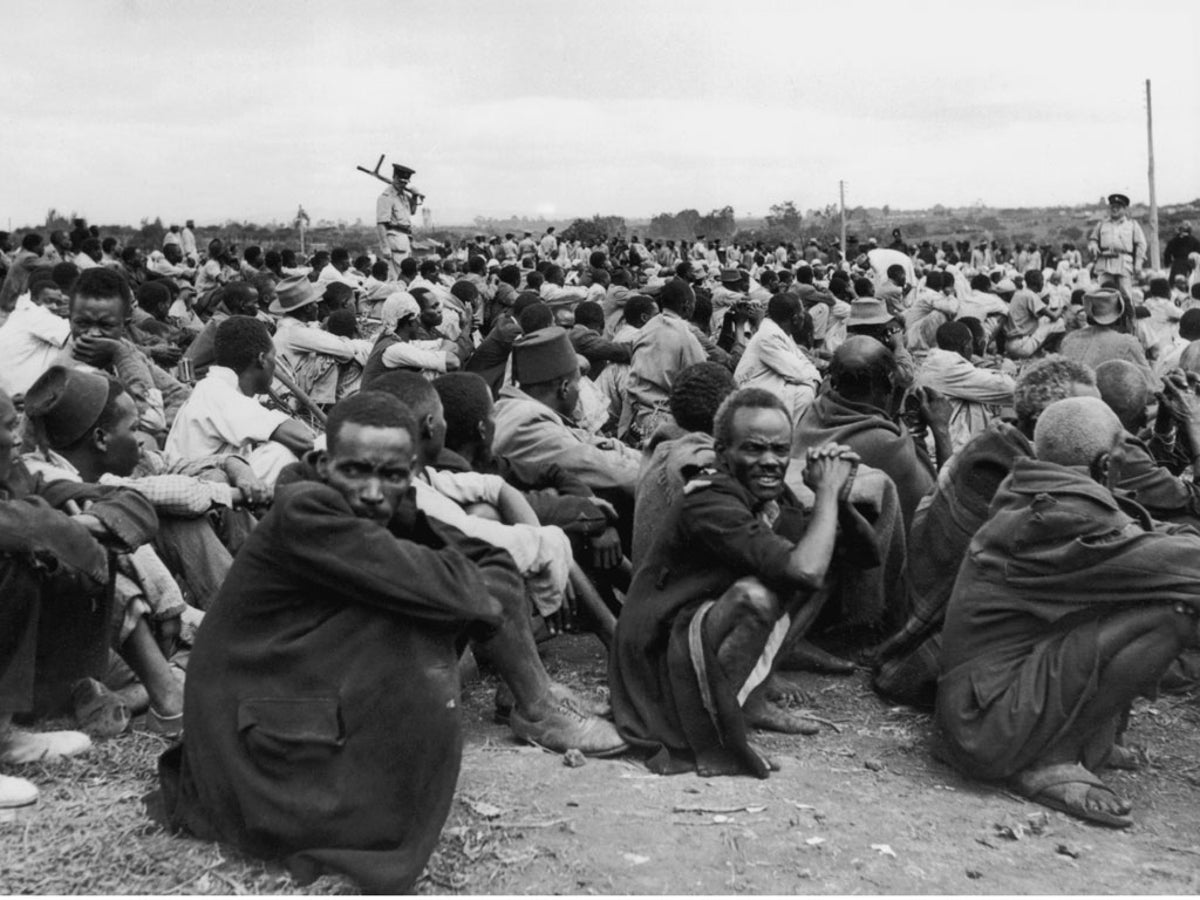

The Mau Mau uprising began in the 1950s among the Kikuyu people of Kenya. The group led a violent rebellion against British colonial rule in Kenya. During the 1950s, the Mau Mau movement was banned by British leaders because of their resistance. In October 1952, following a campaign of violence and killings attributed to the Mau Mau uprising, the British Kenyan authorities declared a state of emergency. It commenced four years of militarism directed against Mau Mau rebels. According to Mwangi (1991), by the end of 1956, more than 11,000 Mau Mau resistors had been killed in the revolt together with approximately one hundred Europeans and two thousand African loyalists. Following these events, over 20,000 other resistors were placed in detention camps where a lot of effort was put into altering their nationalist aspirations to the political perceptions of the British government (Mwangi, 1991). However, despite these efforts, Kikuyu resistance led the Kenyan independence movement, and Jomo Kenyatta, prior to being jailed as a Mau Mau leader in 1953, became the prime minister of the independent country in 1963. Years later, in 2003, the Kenyan government did away with the Mau Mau ban.

The policy of reallocation by the British expropriated fertile land from Kenyan locals handing over land rights to white settlers who mainly arrived from Britain and South Africa. This move marked the beginning of a pattern that would define the relationship between Europeans and Kenyan locals for the first half of the 20th century. The Crown Lands Ordinance Act of 1915 revoked Kenyan locals’ few remaining land rights, thus displacing them off their land, making them an agricultural proletariat. This led to hundreds of thousands of Kenyans living in poverty in the slums of Nairobi and rural areas for decades. The decades of ill-treatment and oppression under British rule formed an atmosphere of bitterness which led to the creation of the Mau Mau uprising.

Specific policies led to the imprisonment of Mau Mau members, including the declaration of the State of Emergency and operation Jock Scott. This operation was a coordinated police movement that resulted in the arrest of one hundred and eighty-seven Kikuyus (Furedi, 1989). These Kikuyus were believed by the government to be leaders of the Mau Mau movement, which mainly included leaders of the KAU movement and the operation Jock Scott missed out on many members of the Mau Mau central committee. The deployment of British troops together with operation Jock Scott disrupted and forced rebels into submission. In addition, British troops began a policy of collective punishment, which was directed at undermining popular support of the Mau Mau. Under this policy, if a local villager was discovered to be a Mau Mau supporter, the whole village was declared as such, thus resulting in the eviction policy.

Following this policy, many Kikuyus were evicted from their homes and were shifted into areas declared as Kikuyu reserves. One specific ugly element of the eviction policy was the utilization of concentration camps to deal with those suspected to have dealings with the Mau Mau. Abuse and torture were common in the camps as British guards utilized beatings, sexual abuse, and killings to get information from the prisoners and force them into renouncing their allegiance to the Mau Mau uprising (Edgerton, 1991).

Following the murder of thirty-two white officials by the Mau Mau, the British responded brutally by detaining approximately 150,000 Kenyans in concentration camps whereby survivors were beaten, tortured, killed, and sexually assaulted (Edgerton, 1991). McGreal (2006) says that more than half a century later, a handful of survivors are suing the British government. Based on a series of interviews carried out on some of the survivors, McGreal (2006) states that the camps were riddled with routine of tortures, beatings, and typhoid, which resulted in the loss of many lives. A regimen referred to as the ‘dilution technique’ was enforced in the camps.

One survivor claims Terence Gavaghan, a colonial official, together with others, beat them from the day they arrived with sticks, fists, and hit them with their boots. They were flogged in the camps, starved, worked to death, tortured, and forced to confess their Mau Mau oaths. The survivors also describe the gross details of how women were raped and sexually abused. They now ask for compensation and an apology for what they perceive as a system of organized cruelty that has never been practiced anywhere else throughout the years of the British Empire (McGreal, 2006).

In 2013, the then foreign secretary, William Hague, announced the UK was paying out £19.9m in costs and compensation to more than 5,228 elderly Kenyans who suffered torture and abuse during the Mau Mau uprising. An additional lawsuit was filed in 2016 with more than 40,000 claimants. That case was dismissed on the grounds that the events are more than 50 years old and out of the state of