Amazon removed this documentary from its collection during Black History Month and offered the producers no explanation. However, the documentary remains available on several other platforms.

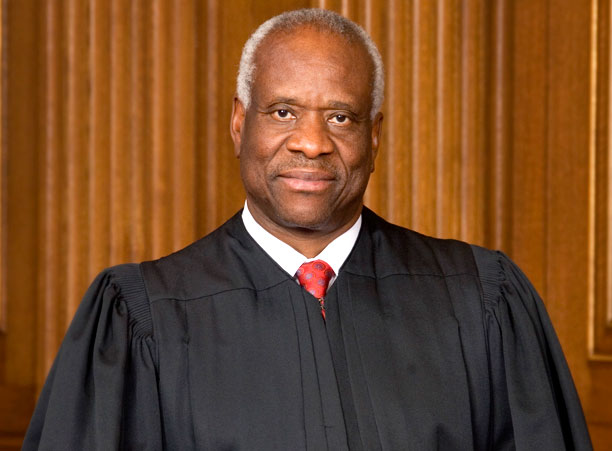

With unprecedented access, the producers interviewed Justice Clarence Thomas and his wife, Virginia, for over 30 hours of interview time, over many months. Justice Thomas tells his entire life’s story, looking directly at the camera, speaking frankly to the audience. After a brief introduction, the documentary proceeds chronologically, combining Justice Thomas’ first person account with a rich array of historical archive material, period and original music, personal photos, and evocative recreations. Unscripted and without narration, the documentary takes the viewer through this complex and often painful life, dealing with race, faith, power, jurisprudence, and personal resilience.

In 1948, Clarence Thomas was born into dire poverty in Pin Point, Georgia, a Gullah- speaking peninsula in the segregated South. His father abandoned the family when Clarence was two years old. His mother, unable to care for two boys, brought Clarence and his brother, Myers, to live with her father and his wife. Thomas’ grandfather, Myers Anderson, whose schooling ended at the third grade, delivered coal and heating oil in Savannah. He gave the boys tough love and training in hard work. He sent them to a segregated Catholic school where the Irish nuns taught them self-discipline and a love of learning. From there, Thomas entered the seminary, training to be a priest.

As the times changed, Thomas began to rebel against the values of his grandfather. Angered by his fellow seminarians’ racist comments following the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. and disillusioned by the Catholic Church’s general failure to support the civil rights movement, Thomas left the seminary. His grandfather felt Thomas had betrayed him by questioning his values and kicked Thomas out of his house. In 1968, Thomas enrolled as a scholarship student at the College of the Holy Cross in Massachusetts. While there, he helped found the Black Student Union and supported the burgeoning Black Power Movement.

Then, Thomas’s views began to change, as he saw it, back to his grandfather’s values. He judged the efforts of the left and liberals to help his people to be demeaning failures. To him, affirmative action seemed condescending and ineffective, sending African-American students to schools where they were not prepared to succeed. He watched the busing crisis in Boston tear the city apart. To Thomas, it made no sense. Why, he asked, pluck poor black kids out of their own bad schools only to bus them to another part of town to sit with poor white students in their bad schools?

At Yale Law School, he felt stigmatized by affirmative action, treated as if he were there only because of his race, minimizing his previous achievements. After graduating in 1974, he worked for then State Attorney General John Danforth in Missouri, eventually working in the Reagan administration, first running the Civil Rights Division of the Department of Education and then the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. In 1990, he became a judge on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit.

In 1991, President George H.W. Bush nominated Clarence Thomas to the Supreme Court. His confirmation hearings would test his character and principles in the crucible of national controversy. Like the Bork hearings in 1987, the Democrats went after Thomas’ record and his jurisprudence, especially natural law theory, but also attacked his character. When that failed, and he was on the verge of being confirmed, a former employee, Anita Hill, came forth to accuse him of sexual harassment. The next few days of televised hearings riveted the nation. Finally, defending himself against relentless attacks by the Democratic Senators on the committee, Thomas accused them of running “a high-tech lynching for uppity blacks who in any way deign to think for themselves, to do for themselves, to have different ideas.” After wall-to-wall television coverage, according to the national polls, the American people believed Thomas by more than a 2-1 margin. Yet, Thomas was confirmed by the closest margin in history, 52-48.

In his 27 years on the court, Thomas’s jurisprudence has often been controversial—from his brand of originalism to his decisions on affirmative action and other hot button topics. Critical journalists often point out that he rarely speaks in oral argument.

The public remains curious about Clarence Thomas—both about his personal history and his judicial opinions. His 2007 memoir, My Grandfather’s Son, was number one on The New York Times’ bestseller list.

In addition to the two-hour feature length documentary film, a companion website providing more details and curriculum materials will be created and available. The website will draw on the over thirty hours of interviews of both Justice Thomas and his wife, most of which did not appear in the film. LEARN MORE