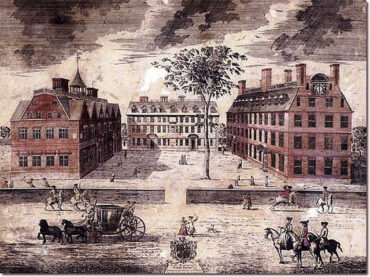

Harvard University has finally admitted to its legacy of slavery and they have the receipts. In 2019, Harvard’s 29th president, Lawrence S. Bacow, established the Presidential Initiative on Harvard & the Legacy of Slavery, appointed a committee representative of all the University’s schools, and charged this group with diving deep into our history and its relationship to the present.

HARVARD’S LEGACY

The story most often told about American slavery focuses on large plantations in the South, forced agricultural labor, and brutal auctions where enslaved people were sold “down the river.” New England is not, in general, a part of this narrative. The Commonwealth of Massachusetts and the City of Boston are, rather, remembered as the birthplace of the American Revolution, and they are typically associated with the antislavery moment. Massachusetts is thought to have been a hotbed of opposition to slavery, and so it was at critical junctures. The Commonwealth can rightly claim noted abolitionists like William Lloyd Garrison, Frederick Douglass, David Walker, and US Senator Charles Sumner (AB 1830; LLB 1833) along with courageous soldiers who fought for the Union during the Civil War—including the famed 54th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry Regiment, commanded by the Harvard alumnus Robert Gould Shaw (Class of 1860; posthumous AB 1873).

This conventional telling—focused on the region’s celebrated roles in the Revolutionary War, the abolitionist struggle, and the preservation of American nationhood during the Civil War—makes valor, social consciousness, and liberty the through lines in New England’s history. Resistance to tyranny in service of American democracy is an integral part of the region’s cultural identity. But history is rarely, if ever, so neat and linear; and reality complicates this incomplete, if popular, narrative.

In fact, slavery thrived in New England from its beginnings, and was a vital element of the colonial economy. Colonists first enslaved and sold Indigenous people, and they dispossessed and massacred Native peoples through war. They also enslaved Africans and played a key role in the Atlantic slave trade, building a thriving economy based on “an economic alliance with the sugar islands of the West Indies.” This trade involved the provision of food, fuel, and lumber produced in New England to plantations of the Caribbean, where those goods were exchanged for tobacco, coffee, and sugar produced by enslaved Africans—or for enslaved people themselves. “This effectively made Boston a slave society,” according to a leading historian of the region, “but one where most of the enslaved toiled elsewhere, sustaining the illusion of Boston in New England as an inclusive republic devoted to the common good.” By 1700, New Englanders had made at least 19 voyages to Africa and then to the West Indies, the chief route of the slave trade, as well as many more voyages between Massachusetts Bay and the Caribbean.

The Massachusetts Bay Colony’s Body of Liberties, written in 1641, made such exchanges lawful. The first legal code governing slavery in British North America, it prohibited “bond-slavery,” “unless it be of lawfull captives, taken in just warrs, and such strangers as willingly sell themselves, or are solde to us,” leading one historian to note, “the word ‘unless’ has seldom carried more baggage.” Even as it paid homage to the Magna Carta, the Body of Liberties permitted the buying, selling, and trading of Indigenous people and Africans. Slavery would not officially end in Massachusetts until 1783.

So, too, was slavery integral to Harvard. Over nearly 150 years, from the University’s founding in 1636 until the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court found slavery unlawful in 1783, Harvard presidents and other leaders, as well as its faculty and staff, enslaved more than 70 individuals, some of whom labored on campus. Enslaved men and women served Harvard presidents and professors and fed and cared for Harvard students. Moreover, throughout this period and well into the 19th century, the University and its donors benefited from extensive financial ties to slavery. These profitable financial relationships included, most notably, the beneficence of donors who accumulated their wealth through slave trading; from the labor of enslaved people on plantations in the Caribbean islands and in the American South; and from the Northern textile manufacturing industry, supplied with cotton grown by enslaved people held in bondage. The University also profited from its own financial investments, which included loans to Caribbean sugar planters, rum distillers, and plantation suppliers along with investments in cotton manufacturing. The balance of the University’s financial ties shifted over time; with the development of industrial capitalism in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the plantation economy evolved, and cotton began to take center stage. Northern textile industrialists interacted with the institution of slavery through the cotton trade; enslaved laborers produced the cotton that was the engine of textile production and, therefore, of the region’s economy. Senator Sumner called this vital economic link between the industrial North and the slaveholding South an “unhallowed alliance between the lords of the lash and the lords of the loom.” READ MORE

SUMMARY OF FINDINGS

- Slavery—of Indigenous and of African people—was an integral part of life in Massachusetts and at Harvard during the colonial era.

- Between the University’s founding in 1636 and the end of slavery in the Commonwealth in 1783, Harvard faculty, staff, and leaders enslaved more than 70 individuals.

- Some of the enslaved worked and lived on campus, where they cared for Harvard presidents and professors and fed generations of Harvard students.

- Through connections to multiple donors, the University had extensive financial ties to, and profited from, slavery during the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries.

- These financial ties include donors who accumulated their wealth through slave trading; from the labor of enslaved people on plantations in the Caribbean islands and the American South; from the sale of supplies to such plantations and trade in goods they produced; and from the textile manufacturing industry in the North, supplied with cotton grown by enslaved people held in bondage in the American South. During the first half of the 19th century, more than a third of the money donated or promised to Harvard by private individuals came from just five men who made their fortunes from slavery and slave-produced commodities.

- These donors helped the University build a national reputation, hire faculty, support students, grow its collections, expand its physical footprint, and develop its infrastructure.

- The University today memorializes benefactors with ties to slavery across campus through statues, buildings, professorships, student houses, and the like.

- While some Harvard affiliates fought against human bondage, on several occasions Harvard leaders, including members of the Harvard Corporation, sought to moderate or suppress antislavery politics on campus and among prominent Harvard affiliates.

- From the mid-19th century well into the 20th, Harvard presidents and several prominent professors, including Louis Agassiz, promoted “race science” and eugenics and conducted abusive “research,” including the photographing of enslaved and subjugated human beings. These theories and practices were rooted in racial hierarchies of the sort marshalled by proponents of slavery and would produce devastating consequences in the 19th and 20th centuries. Records and artifacts documenting many of these activities remain among the University’s collections.

- Research to advance eugenic theories also took place on campus: Dudley Allen Sargent, director of the Hemenway Gymnasium from 1879 until 1919, implemented a “physical education” program that involved intrusive physical examinations, anthropometric measurements, and the photographing of unclothed Harvard and Radcliffe students. Archives documenting Sargent’s activities remains among the University’s collections.

- Among Harvard’s vast museum collections are the remains of thousands of individuals. Many of these human remains are thought to belong to Indigenous people, and at least 15 are individuals of African descent who may have been enslaved, two of whom also had Indigenous ancestry. President Bacow has established a Steering Committee on Human Remains in Harvard Museum Collections to address this finding.

- Legacies of slavery persisted at Harvard, and throughout American society, after the Constitution and laws officially proscribed human bondage. Such legacies, including racial segregation, exclusion, and discrimination, were a part of campus life well into the 20th century.

- Many esteemed Black graduates of Harvard and of Radcliffe aided the nation and their communities through activism, teaching, legal advocacy, and community service devoted to the eradication of racism and to equal opportunity.

- The achievements of Black graduates of Harvard and of Radcliffe illustrate the entwining of the nation’s racial progress and access to a Harvard, and a Radcliffe, education.